Webinar

Completing projects on target: Ready, steady... GoTechnology!

This is the third article in our series focused on the work Wood is doing in partnership with the United Nations (UN) to support the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

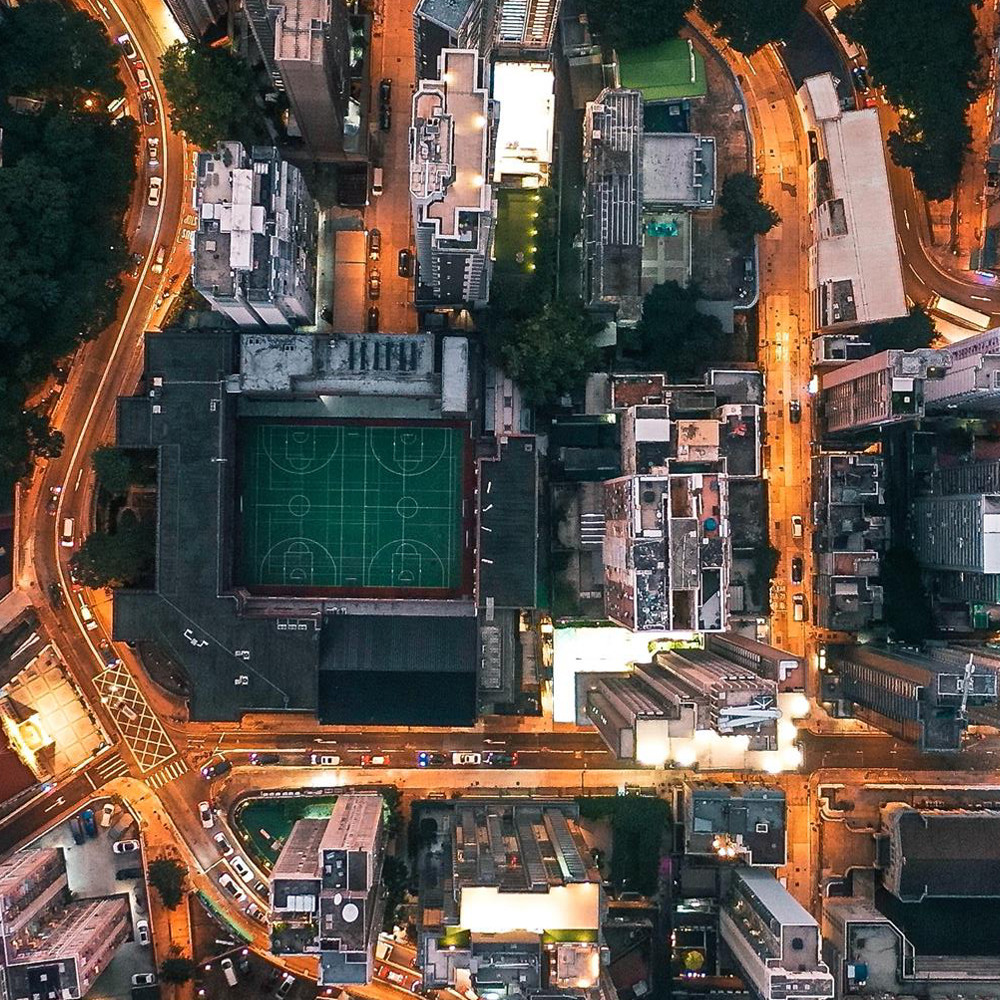

At the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, typically bustling city streets across the world were unimaginably empty. As people took shelter in their homes under widespread lockdowns, rush-hour congestion vanished and traffic-related emissions, like carbon dioxide and nitrogen dioxide, dropped to unprecedented levels.

Smog-filled skylines once darkened by air pollution began to turn blue in some of the globe’s most polluted cities, including Delhi, Beijing and Milan – providing a rare glimpse of a world with clean air.

Although air quality dramatically improved in 84% of nations worldwide, the new reality was only temporary. As many countries lifted strict lockdowns and pushed an aggressive rollout of the COVID-19 vaccine, eerily-vacant roadways again became crowded with vehicles as cities sought to forge a gradual return to normalcy.

With more cities emerging from the grip of the pandemic, some are already seeing a surge in air pollution, including metropolitan areas across Europe. More than half of European cities are exposed to air containing dangerous levels of fine particulate matter (PM2.5), according to new data by the European Environment Agency (EEA). PM2.5 is an air pollutant that has the highest impact on human health.

Only 127 of the 323 cities surveyed had passable air conditions under the annual guideline value of the World Health Organisation. Umeå, Sweden and Tampere, Finland had the cleanest air, while Nowy Sącz, Poland and Cremona, Italy had the worst air quality.

As the leading environmental health risk in Europe, air pollution can lead to respiratory and cardiovascular diseases and lung cancer, causing 400,000 premature deaths annually. To tackle this challenge, the European Union launched the Second Clean Air Outlook report, which focuses on the potential to reduce the number of premature deaths resulting from air pollution by 55% in 2030 by regulating sources of air pollution and minimising the impacts of climate change.

In alignment with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal No 3 and target 11.6, the EU’s air pollution data centre, the EEA, has been working for decades to develop long-term strategies to lower hazardous emissions of air pollutants by providing detailed assessments to policy makers. Currently, Wood is working with the EEA to map information on the environmental burden of disease and best practices for shrinking and managing exposure to poor air quality in European cities.

Our team will also develop case studies of measures, implemented under the Air Quality Directive (2008/50/EC) to improve urban air quality. Each study will focus on reducing emissions from mobility, energy, industrial and agricultural sectors. This work will help strengthen the EEA’s knowledge of good practices in mitigating air pollution, as well as inform the progress towards achieving the ambitions for tackling unhealthy air outlined in the European Green Deal.

The investigation into best practices further builds on previous assessments Wood created for the European Parliament to assess the adoption of air policies in a sample of 10 urban agglomerations. By drawing on key lessons learned from the pandemic, we provided a detailed picture of the effectiveness of differentiated strategies to better protect public health and the environment and pave the way for cleaner air.